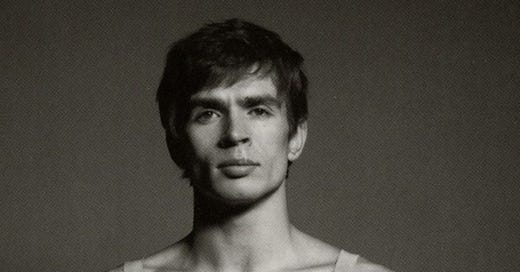

“He was a dancer like any other dancer. It is extraordinary to have 19 points out of 20. It is extremely rare to have 20 out of 20. However, to have 21 out of 20 is even much rarer. And this was the situation with Nureyev.”

— Pierre Bergé

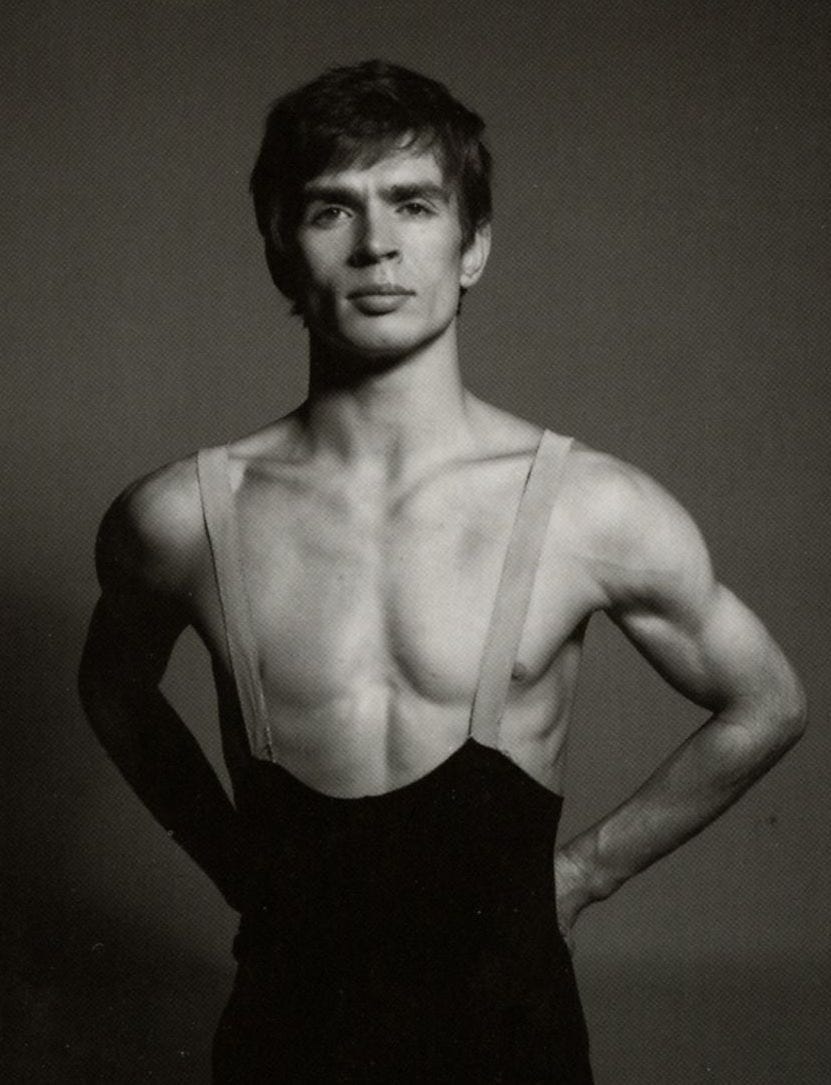

Rudolf Nureyev was a ballet dancer who revolutionised the male role in classical ballet. His performances were known for their fiery temperament, emotional intensity, and precise technique, blending classical purity with a bold athleticism and expressive freedom that electrified audiences worldwide.

Table of Contents: Early Life and Beginnings / Ufa / Leningrad / Kirov Ballet / Defection and Rise to Stardom / Post-Defection Ballet Career / The Nijinsky-Lifar-Nureyev Arch / Directing Career / Personal Life / Later Years

If you aren’t subscribed yet, hit the subscribe button below to receive the Adorable Stories every weekend, directly in your inbox:

Early Life and Beginnings

“My mother was born in the beautiful ancient city of Kazan. We are Muslims. Father was born in a small village near Ufa, the capital of the Republic of Bashkiria. Thus, on both sides our relatives are Tatars and Bashkirs. I cannot define exactly what it means to me to be a Tatar, and not a Russian, but I feel this difference in myself. Our Tatar blood flows somehow faster and is always ready to boil”

— Rudolf Nureyev

Born on March 17th, 1938, aboard a Trans-Siberian train near Lake Baikal, Rudolf Khametovich Nureyev came into the world traveling—a fitting start for someone whose life would be marked by constant movement.

He was of Tatar descent and raised initially in poverty-stricken conditions near Ufa, Bashkir ASSR (part of the Soviet Union at the time).

Rudolf Nureyev’s parents were Hamet Nureyev and Farida Nureyeva. His father, Hamet, served as a political commissar in the Soviet Red Army and later as a security officer. His mother, Farida, was a homemaker who cared for Rudolf and his siblings through challenging times, including hardships and wartime difficulties.

Ufa

The family lived modestly on the outskirts of Ufa where Nureyev spent his early childhood years. Neither of his parents had any sort of ties to ballet, music or performing arts in general, making his journey into ballet even more remarkable and unexpected.

It was in Ufa that Rudolf first discovered ballet, when his mother took him and his sisters to local folk-dance shows.

Despite extremely limited resources and the absence of prestigious training schools in Ufa, he showed exceptional promise from the start. His natural talent, fierce determination, and tireless practice quickly outgrew what local teachers could offer.

Albeit his first performances took place in modest settings, even then, his extraordinary ability and charisma stood out, catching the attention of visiting dance teachers who encouraged him to pursue formal ballet training.

Leningrad

As a teenager, young Rudolf joined a local ballet company in Ufa. On a tour stop in Moscow, he auditioned for the Bolshoi ballet company and was accepted. However, he felt that the Kirov Ballet school was better for his career, so he left his local touring company and bought a train ticket to Leningrad.

“I approach dancing from a different angle than those who begin dancing at eight or nine. Those who have studied from the beginning never question anything.”

— Rudolf Nureyev

At age 17, in 1955, he enrolled in the prestigious Vaganova Ballet Academy in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg): normally dancers who usually become principal dancers, entered the Vaganova school at nine years old and went through the full nine years of dance education. Rudolf graduated in three.

Rudolf’s talent was clear, and so was his rebellious spirit.

This academy was (and still is) famously associated with the Kirov (now Mariinsky) Ballet: the ballet master at the Vaganova, Alexander Ivanovich Pushkin, took an interest in him professionally and allowed Rudolf to live with him and his wife.

Roughly a year into his rigorous training at the Vaganova Ballet Academy, Rudolf sustained a career threatening knee-ligament injury: this painful setback threatened his dance career and might have prematurely ended his aspirations.

Rather than undergoing surgery —which at the time carried significant risks for a dancer to permanently end a ballet career— Rudolf embarked on a disciplined, conservative recovery program. Through dedicated physical therapy, targeted knee strengthening exercises, patient rehabilitation, and sheer determination, he gradually restored his strength and flexibility. This challenging period of recovery highlighted the young Rudolf’s remarkable resolve and resilience, qualities that would remain hallmarks throughout his legendary career.

Kirov Ballet

Upon his graduation in 1958 from the Vaganova Academy, Nureyev joined the Kirov Ballet: notwithstanding his young age, he was given solo roles as a principal dancer from the outset.

Nureyev regularly partnered with Natalia Dudinskaya (26 years his senior), the company’s senior ballerina and wife of its director, Konstantin Sergeyev.

“When I miss class for one day, I know it. When I miss class for two days, my teacher knows it. When I miss class for three days, the audience knows it.”

—Rudolf Nureyev

Before long, Nureyev became one of the Soviet Union’s best-known dancers: from 1958 to 1961, in his three years with the Kirov, he danced a total of 15 different roles and quickly became a ballet sensation and one of the Soviet Union most prized instruments of propaganda to demonstrate its alleged “cultural supremacy” over the West, so much that the Soviet’s Ministry of Culture informed him personally that he would not be allowed to travel abroad after 1961.

Defection and Rise to Stardom

Nureyev’s big moment came in June 1961.

During a tour of Europe with the Kirov Ballet Company in Paris, Rudolf made a dramatic decision that altered his life forever.

After performing successfully in Paris, Nureyev and the Kirov Ballet company were scheduled to fly to London and continue touring across Western Europe: however, Soviet authorities had grown increasingly wary of Rudolf’s independent behavior (he was noticed frequenting high-profile friends in Paris), friendships with Western artists, and his openness toward Western culture (the KGB spotted him in some of Paris most famous gay bars).

At the Le Bourget Airport, just before boarding their flight to London, Soviet KGB agents suddenly informed Nureyev he would be separated from the rest of the Kirov Ballet company and instead return immediately to Moscow—supposedly to perform at a special gala at the Kremlin.

Rudolf was immediately suspicious of this abrupt change in the travel plan by the Soviet security agents, and sensed he had been spied and would be punished in Moscow for his interactions with Westerners while in Paris.

In a split moment of panic and resolve, he refused to board the Moscow-bound plane.

The KGB agents tried firmly to coerce him — claiming that actually his mother was gravely hill and was waiting for him in Moscow — urging and physically guiding him toward the aircraft, but they stopped short of using overt violence, fearing negative publicity.

Amid the confusion, Rudolf appealed desperately to French airport police, requesting political asylum: French officers immediately stepped in, calmly but firmly separating him from the Soviet officials, and granting him protection.

This bold, split-second decision altered Nureyev’s destiny forever, marking one of the highest-profile defections of the Cold War era and symbolizing a powerful personal and artistic rebellion against Soviet oppression and censorship.

His defection made headline news worldwide, making him instantly famous, not just as an exceptional dancer but as a symbol of artistic and personal freedom during the height of the Cold War.

For Rudolf, it was not merely a rejection of his homeland, but rather an embrace of a broader artistic world, one where his talent was allowed to flourish without constraints or censorship.

Post-Defection Ballet Career

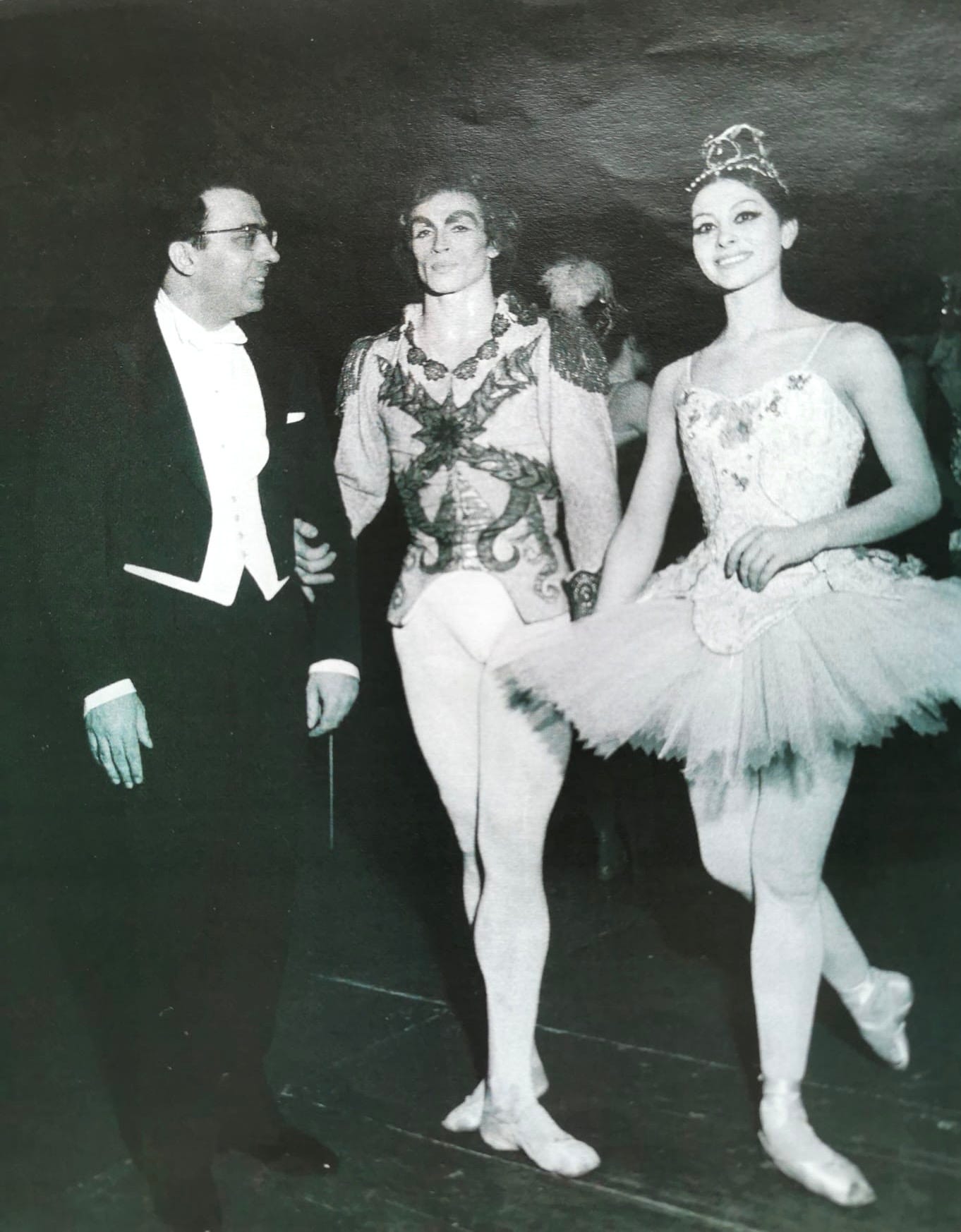

After his dramatic defection to the West in June 1961, Rudolf Nureyev quickly began dancing with the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas in Paris. His performances there immediately showcased his passionate style, technical brilliance, and powerful stage presence, helping him build a strong reputation in Western ballet circles.

Shortly thereafter, he was invited to perform with London’s prestigious Royal Ballet, where he famously partnered with prima ballerina assoluta Dame Margot Fonteyn (almost twenty years his senior).

“I don’t care if Margot is a Dame of the British Empire or older than myself. For me she represents eternal youth; there is an absolute musical quality in her beautiful body and phrasing. Because we are sincere and gifted, an intense abstract love is born between us every time we dance together.”

—Rudolf Nureyev

At the Royal Ballet, their electrifying partnership in productions such as Giselle, Swan Lake, and Romeo and Juliet captivated international audiences and became legendary in ballet history.

Nureyev also frequently guest-performed with the American Ballet Theatre (ABT) in New York which allowed him to partner with Gelsey Kirkland, Cynthia Gregory, and Patricia Ruanne, delighting American audiences and critics alike.

“He was not only an exceptional dancer but also a musician and conductor, so much so that when I got on the piano he even helped me turning the pages. There has always been great harmony and collaboration.”

— Maestro Paolo Peloso, Orchestra Conductor at Teatro La Scala, Milan — from an interview with the Author.

At La Scala Ballet in Milan, Rudolf not only performed classical roles but also choreographed and restaged ballets, deepening his engagement with the creative side of dance.

The Nijinsky-Lifar-Nureyev Arch

Vaslav Nijinsky (1889-1950), Serge Lifar (1905-1986) and Rudolf Nureyev each profoundly shaped ballet through their uniquely distinctive artistic styles and approaches to dance.

Nijinsky, active primarily in the early 20th century, astonished audiences with his remarkable elevation, powerful leaps, and unprecedented dancing expressiveness. His deeply emotional and often provocative interpretations with the Ballets Russes, along with groundbreaking choreography such as The Rite of Spring and Afternoon of a Faun, pushed ballet into modernity and challenged its long-established norms.

Serge Lifar, Nijinsky’s successor at the Ballets Russes and later director of the Paris Opera Ballet, brought elegance, refined lyricism, and sculptural clarity to his dancing and choreography. Lifar sought harmony between classical purity and contemporary sensibilities, emphasizing the beauty of line, clarity of form, and sophisticated grace.

Rudolf Nureyev, emerging decades later in the mid-20th century, combined intense passion, dramatic charisma, and technical mastery, forever redefining the male role in classical ballet. His performances were known for their fiery temperament, emotional intensity, and precise technique, blending classical purity with a bold athleticism and expressive freedom that electrified audiences worldwide.

While Nijinsky revolutionized ballet through modernist experimentation and emotional daring, Lifar brought a refined neoclassical aesthetic and Nureyev revitalized it through dramatic intensity and technical brilliance: each dancer uniquely advanced ballet’s expressive possibilities and permanently influenced its evolution.

Directing Career

From 1983 to 1989, Rudolf Nureyev served as the artistic director of the prestigious Paris Opera Ballet, a position through which he profoundly influenced the company’s identity and international reputation.

As director, Nureyev brought his characteristic rigor, discipline, and innovative vision to the company, emphasizing precision, expressive dancing, and a renewed focus on classical repertoire.

He meticulously restaged numerous classic ballets —including his acclaimed versions of Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty, Raymonda, and La Bayadère— infusing them with fresh choreographic insights, vibrant energy, and dramatic power.

Under his guidance, the Paris Opera Ballet experienced a notable artistic renaissance, reclaiming its status as one of the world’s leading ballet companies. Nureyev was also instrumental in instructing young talent, inspiring dancers to achieve new heights of artistic excellence and technical skill.

Although his directorship was often demanding and occasionally controversial due to his uncompromising standards and intense work ethic, the lasting legacy of his tenure remains evident in the company’s continued prominence, rich classical repertoire, and international acclaim.

Personal Life

“Of course I have a personal life.”

— Rudolf Nureyev

Rudolf Nureyev’s personal life was marked by extreme privacy.

Openly gay in an era of widespread homophobia, he navigated relationships discreetly to safeguard his career and reputation.

His most enduring partnership was with Danish dancer Erik Bruhn, a relationship spanning over 25 years that blended mutual artistic admiration with deep emotional connection.

Nureyev’s magnetic personality drew him into elite social circles, mingling with celebrities like Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, her sister Lee Bouvier, Freddie Mercury, Ringo Starr, Gore Vidal (extensively featured in the Adorable Story #99) and Andy Warhol, yet he fiercely guarded his private affairs.

Thanks to his legendary performances across the world, he became substantially wealthy and cultivated a lavish lifestyle, amassing art, antiques, and properties across the globe, including a celebrated apartment at 23 Quai Voltaire, on the Rive Gauche in Paris (designed by Emilio Carcano), a villa above Monte-Carlo, a London house, an apartment in the Dakota building in New York, a ranch in Virginia, home on Saint Barthélemy’s in the Caribbean and a villa on the secluded island of Li Galli (between Capri and the Amalfi Coast), previously owned by Léonide Massine, the choreographer of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes.

Later Years

Rudolf Nureyev was diagnosed with HIV in 1984, a time when the virus was poorly understood and heavily stigmatized.

He initially kept his diagnosis private, fearing professional repercussions and public scrutiny. As AIDS therapies were still in their infancy, Nureyev sought experimental treatments, including early antiretroviral drugs like AZT (approved in 1987) and therapies at the world famous Pasteur Institute in Paris, where he resided.

For several years, Nureyev simply denied that anything was wrong with his health: he continued performing into the late 1980s, though his condition gradually limited his appearances and his diminished capabilities disappointed his admirers who had fond memories of his outstanding prowess and skill.

In 1986, his long-term partner Erik Bruhn died in Toronto, officially of lung cancer (albeit some recent sources claim he may have died of AIDS instead) and his death profoundly affected Rudolf.

Although he petitioned the Soviet government for many years to be allowed to visit his mother, he was not allowed to do so until 1987, when his mother was dying and Mikhail Gorbachev personally consented to the visit.

His health marked a visible decline in summer 1991 and by 1992, Rudolf’s illness became public, drawing attention to the AIDS crisis within the arts community.

Rudolf Nureyev succumbed to cardiac complications linked to AIDS on January 6th, 1993: he was only 54.

—Alberto @

Do you know anyone who would love to read this Adorable Story? Show your support by sharing Adorable Times’ Newsletter and earn rewards for your referrals.