“The four most beautiful words in our common language: I told you so.”

— Gore Vidal

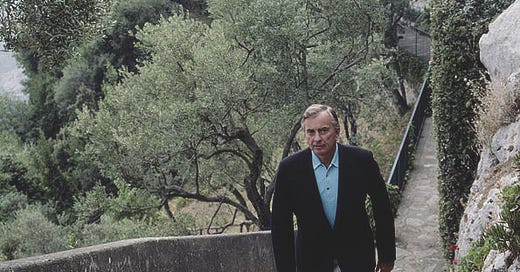

Gore Vidal was one of the most fascinating and provocative writers of the 20th century. Known for his biting wit, masterful prose, and sharp social commentary, Vidal left an indelible mark on literature, politics, and culture.

His life was characterized by literary brilliance, controversy, and a fearless dedication to challenging societal norms.

Table of Contents: Early Years / World War II Service / Life After World War II / Recovery and Reinvention / Wealth and Financial Independence / Camelot / Literary Achievements / Legendary Feuds / Personal Life / Later Years

If you aren’t subscribed yet, hit the subscribe button below to receive the Adorable Stories every weekend, directly in your inbox:

Early Years

“Even as a boy, I was always aware of the distance between myself and others. I watched, I observed, I listened—but I kept my own counsel.”

— Gore Vidal

Gore Vidal was born on October 3rd, 1925, at the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York.

His father, Eugene Luther Vidal, was a pioneering aeronautics instructor and government official, while his mother, Nina Gore, came from a politically connected family.

Gore Vidal’s maternal grandfather, Thomas Pryor Gore, was a U.S. Senator from Oklahoma, and his family connections extended into the circles of Washington’s elite.

Given the Senator’s blindness, young Gore Vidal read aloud to him, was his grandfather’s Senate page, and his seeing-eye guide throughout Washington.

Vidal’s early years were shaped by his exposure to politics and literature, but also by a sense of independence.

He attended St. Albans School in Washington, D.C., where he began to develop his interest in literature and politics.

Afterward, he enrolled at Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, one of the most elite prep schools in the United States. At Exeter, Vidal contributed to The Exonian, the school newspaper and demonstrated a precocious understanding of language and storytelling.

Vidal did not attend university, a decision he later described as fully deliberate. Instead, he chose to focus on writing and intellectual pursuits.

His early education, combined with his keen observational skills, laid the foundation for his lifelong engagement with history, politics, and culture.

World War II Service

“In the Aleutian Islands, I learned solitude. There is no lonelier place on earth. The fog, the endless rain, the isolation—it was the perfect training ground for a writer.”

— Gore Vidal

During WWII, Vidal enlisted in the U.S. Army at age 17 and served for three years as a warrant officer stationed in the Aleutian Islands, a remote and strategically critical chain of islands in Alaska, near the Bering Strait. The Aleutians were an inhospitable and dangerous post, often referred to as “the Forgotten War” due to its harsh climate and relative isolation.

Vidal’s role in the Army involved working on supply ships in the region, which were tasked with transporting essential goods and personnel.

The extreme weather conditions and grueling monotony of the Aleutian campaign left a deep impression on Vidal, giving him a firsthand view of the physical and psychological challenges of war.

It was during this time that Vidal began writing his first novel, “Williwaw” (1946), drawing directly from his experiences in the Aleutians.

“The williwaw came like a thief in the night, stealing what little calm we had managed to find, leaving chaos in its wake.”

The novel’s title refers to a sudden and violent windstorm common to the region, a metaphor for the unpredictability of war. The book was praised for its realism and mature style, especially remarkable given Vidal’s young age (he was only 19 years old at the time of writing it).

His time in the military instilled a lifelong skepticism about war and its frequent glorification, themes that would reappear again and again throughout his essays and novels.

Life After World War II

After returning from World War II, Gore Vidal focused on establishing himself as a writer.

The success of his debut novel earned him recognition as a serious literary talent.

His second novel, “In a Yellow Wood”, received modest reviews, and did not achieve the same level of impact as his debut novel, though.

However, Gore Vidal did not give up and decided to break significant cultural taboos with the publication of his third novel, “The City and the Pillar” in 1948.

The book, one of the first American novels to openly explore homosexuality, tells the story of a young man, Jim Willard, and his unrequited love for a childhood friend. Vidal portrayed Jim’s sexuality with frankness and without moral condemnation—a revolutionary approach at the time.

However, the novel caused an uproar at the time: many critics and reviewers were scandalized by its subject matter and the neutral tone Vidal adopted toward homosexuality, which challenged the prevailing norms that treated same-sex attraction as either deviant or tragic.

The backlash was swift and severe. Major publications, including The New York Times, ignored or refused to review his subsequent books. As a consequence, Vidal was effectively blacklisted by parts of the literary establishment.

For a writer of his age and ambition, this ostracism could have been career-ending: however, Vidal quickly pivoted to other forms of writing, including screenplays, television scripts, and plays, which allowed him to support himself financially and maintain his creative output.

His commercial work in Hollywood, including contributions to films like “Ben-Hur” (1959, uncredited), helped him recover from the financial and professional damage caused by the controversy.

Recovery and Reinvention

Vidal’s ability to adapt was crucial in overcoming the backlash. During the 1950s, he also began writing under pseudonyms, producing a series of popular mystery novels as Edgar Box (1952-1954), which were financially successful.

These works allowed him to sustain himself while continuing to write more literary material. By the late 1950s, Vidal’s wit, intelligence, and resilience had restored his reputation.

His play “The Best Man” (1960), which dissected the moral compromises of American politics, was a Broadway hit and solidified his status as a prominent cultural figure.

His essays, which he began publishing more frequently in the 1960s on publications like The Nation, The New York Review of Books, Esquire and Encounter (among others), also played a key role in his recovery, earning him critical acclaim and reintroducing him as a major voice in American literary circles.

Wealth and Financial Independence

“Style is knowing who you are, what you want to say, and not giving a damn.”

— Gore Vidal

Vidal’s family background was one of privilege, but it was not without financial instability.

His father, Eugene Luther Vidal, was a prominent figure in aviation (in the 1930s he met and became the great love of the legendary aviator Amelia Earhart), and his mother, Nina Gore, came from a wealthy and politically connected family (she also had “a long off-and-on affair” with the actor Clark Gable).

However, his parents divorced in 1935, when he was young, and there were periods of financial uncertainty, particularly after his mother remarried multiple times.

Though Vidal benefited from his family’s social connections and was educated at elite institutions like St. Albans and Phillips Exeter, he was not independently wealthy in his early years.

After World War II, Vidal was able to support himself entirely through his writing.

By the 1960s, and notwithstanding the effective blacklisting after his third novel a decade earlier, his success as an essayist, playwright, and novelist enabled him to live comfortably, often in luxurious settings.

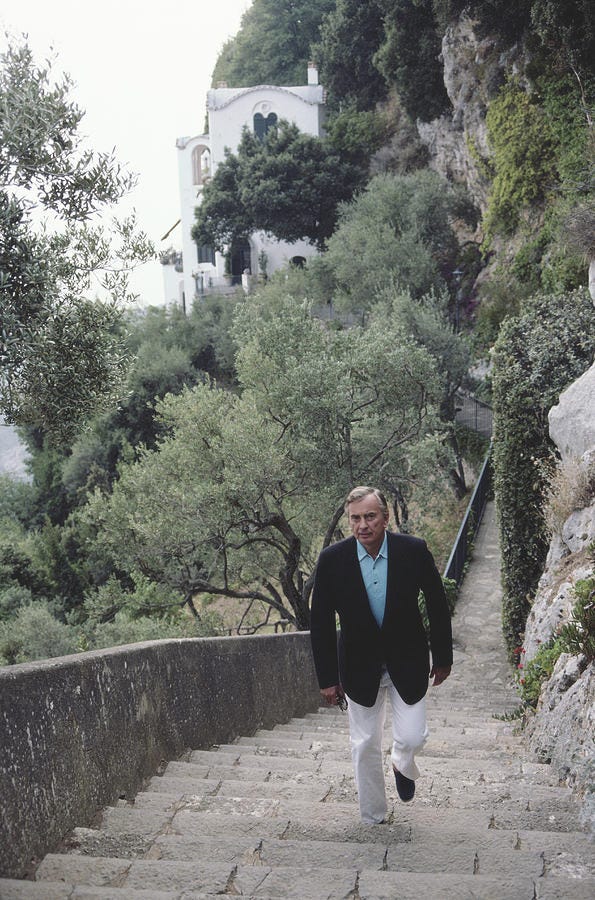

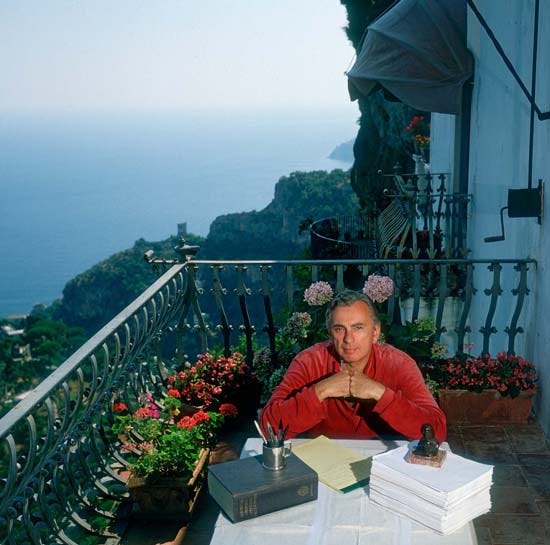

By the 1970s, Vidal sold his home in upstate New York and split his time between homes in Italy (notably his villa “La Rondinaia” in Ravello on the Amalfi Coast, which became a legendary gathering place for celebrities, writers, and political figures, including Tennessee Williams, Paul Newman and Mick Jagger) and on the Hollywood Hills in Los Angeles, funded entirely by his prolific literary and screenwriting work.

He prided himself on being financially independent, once remarking:

“I’m the only writer of my generation who made a living solely from writing.”

Camelot

“Jackie once said to me, ‘They’ll never forgive Jack for being young and handsome and witty.’ But that’s exactly what people remember about him, not what he actually did.”

— Gore Vidal

During this postwar period, Vidal also became personally connected to the Kennedy family.

His mother, Nina, had married Hugh D. Auchincloss Jr., who later became Jacqueline Kennedy’s stepfather, making Vidal a step-relative to the future First Lady.

This connection brought Gore Vidal into the social orbit of John F. Kennedy, whom he admired despite their political differences. Vidal was a frequent guest at the White House during Kennedy’s presidency and maintained a cordial — albeit occasionally strained — relationship with the family.

In particular, Gore Vidal admired John F. Kennedy’s charisma, intelligence, and political acumen, but he was deeply critical of Kennedy’s approach to foreign policy and of the whole concept of Pax Americana.

Vidal believed that Kennedy, despite his progressive image, perpetuated the United States’ aggressive Cold War posture, which Vidal saw as imperialistic and dangerous.

He criticized Kennedy’s handling of the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961, calling it a “reckless” and “poorly conceived” attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro’s government in Cuba.

Vidal also disapproved of Kennedy’s escalation of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, which he viewed as unnecessary meddling in a conflict with little relevance to national security.

Vidal, a staunch critic of American interventionism, argued that Kennedy’s foreign policy reflected a continuation of what he termed the “national security state,” a system in which military and corporate interests dictated U.S. global actions.

While Vidal acknowledged Kennedy’s brilliance as a politician, he saw his foreign policies as inconsistent with the ideals of peace and diplomacy that Vidal himself championed.

Literary Achievements

“We write to remember our lives, to give them shape and meaning, to leave behind some trace of what we were.”

Gore Vidal, Julian, Chapter 9

Vidal’s literary career began early. At the age of 21, he published his first novel, “Williwaw” (1946).

Over the following decades, Vidal wrote more than 25 novels, numerous essays, screenplays, and plays. Some of his most notable works include:

“The City and the Pillar” (1948): A groundbreaking novel that openly addressed homosexuality, a rare and controversial topic at the time. The novel was dedicated to “J. T.”; decades later, Vidal confirmed that the initials were those of his boyhood friend and St. Albans classmate, James Trimble III, killed in the Battle of Iwo Jima on March 1st, 1945, and that Trimble was the only person he ever loved.

“Julian” (1964): A historical novel that tells the story of Julian the Apostate, the Roman Emperor who tried to restore paganism in the 4th century after the empire had largely embraced Christianity. The novel is framed as a fictional memoir written by Julian himself, interspersed with commentary from two of his contemporaries, the scholars Libanius and Priscus. Vidal explores Julian’s rise to power, his philosophical and religious struggles, and his ambitious (but doomed) efforts to revive the ancient gods and Hellenistic traditions, which he believed were superior to Christianity.

“Myra Breckinridge” (1968): A satirical exploration of gender and sexuality, which challenged societal norms and became a cult classic.

“Burr” (1973), “1876” (1976) and “Lincoln” (1984): Part of his acclaimed series of historical novels, these works reimagined key figures and events in American history with a mix of fact, fiction, and biting humor.

Vidal was also a prolific essayist, earning widespread acclaim for his collections such as “United States: Essays 1952–1992”, which won the National Book Award in 1993. Through his essays, he dissected topics ranging from politics and literature to cultural trends, always with his trademark wit and incisiveness.

Legendary Feuds

“Every time a friend succeeds, I die a little.”

— Gore Vidal

Gore Vidal was notorious for his sharp wit and cutting remarks, which led to several high-profile feuds with other prominent figures, including Norman Mailer, Truman Capote, and William F. Buckley Jr.

His long-running feud with Norman Mailer was fueled by their reciprocal disdain and competing egos, with Mailer once headbutting Vidal backstage at The Dick Cavett Show in 1971 after Vidal compared him to Charles Manson in an essay.

Vidal’s rivalry with Truman Capote was equally venomous, as the two traded barbs for decades; Vidal dismissed Capote as a social climber and a writer of “gossip,” while Capote famously quipped that Vidal had “ruined every relationship he ever had by turning it into a competition.”

However, Vidal’s most infamous feud was with conservative commentator William F. Buckley Jr., culminating in their heated exchange during the 1968 televised debates for ABC News. When Vidal called Buckley a “crypto-Nazi,” Buckley responded by calling Vidal a “queer” and threatening to punch him.

The incident became a defining moment in televised debates and cemented their mutual hostility, with both men continuing to attack each other in print for years afterward.

Personal Life

Gore Vidal’s personal life was unconventional and marked by his rejection of traditional ideas about relationships and sexuality.

Though Vidal identified as bisexual and had numerous relationships and affairs throughout his life, he maintained a lifelong partnership with Howard Austen, a former advertising executive.

The two met in 1950, and their relationship lasted over five decades.

The couple lived together primarily at Vidal’s luxurious homes, including Edgewater, a historic mansion in upstate New York, and later at La Rondinaia, in Ravello.

Howard Austen passed away in 2003 from brain cancer, an event that deeply affected Vidal.

After Austen’s death, Vidal reportedly grew increasingly melancholic and reflective, with many observers noting that his loss marked the beginning of Vidal’s own decline in health and spirit.

Later Years

“We have ceased to be a republic long before September 11th, 2001. We are an oligarchy in which a few very rich people manage to control the public through their ownership of the media.”

— Gore Vidal, Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace

After 9/11, Gore Vidal became an outspoken critic of the American Government, which in his opinion used fear to curtail rights, expand surveillance, and centralize power. He was particularly critical of the Patriot Act, and other post-9/11 measures, which he saw as tools to consolidate government control under the guise of national security.

In his later years, Gore Vidal remained an outspoken public intellectual, continuing to write essays, give interviews, and critique American politics and culture with his signature wit and sharpness.

However, as he aged, his health began to decline, and he struggled with physical ailments, including complications from a hip injury that left him reliant on a wheelchair.

Despite these challenges, he continued to publish essays and memoirs, including “Point to Point Navigation” (2006), a sequel to his earlier memoir “Palimpsest” (1995), both of which offered candid reflections on his life, career, and relationships.

Vidal sold Villa La Rondinaia in 2004 and spent much of his later years in Los Angeles, where he passed away on July 31st, 2012, at the age of 86, from complications of pneumonia.

Vidal’s ashes were buried alongside Howard Austen’s in Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

—Alberto @

Do you know anyone who would love to read this Adorable Story? Show your support by sharing Adorable Times’ Newsletter and earn rewards for your referrals.