In the whirlwind world of sherry, one man's name raised above all others like a fine Amontillado over a sea of bland wines: José Ignacio Domecq.

Don José Ignacio Domecq (born in Jerez, Spain on 31 July 1914) was the acknowledged king of sherry tasters and known as El Nariz, "The Nose", for his astonishing ability to sniff out the nuances in the creation of his family's wonderful sherries.

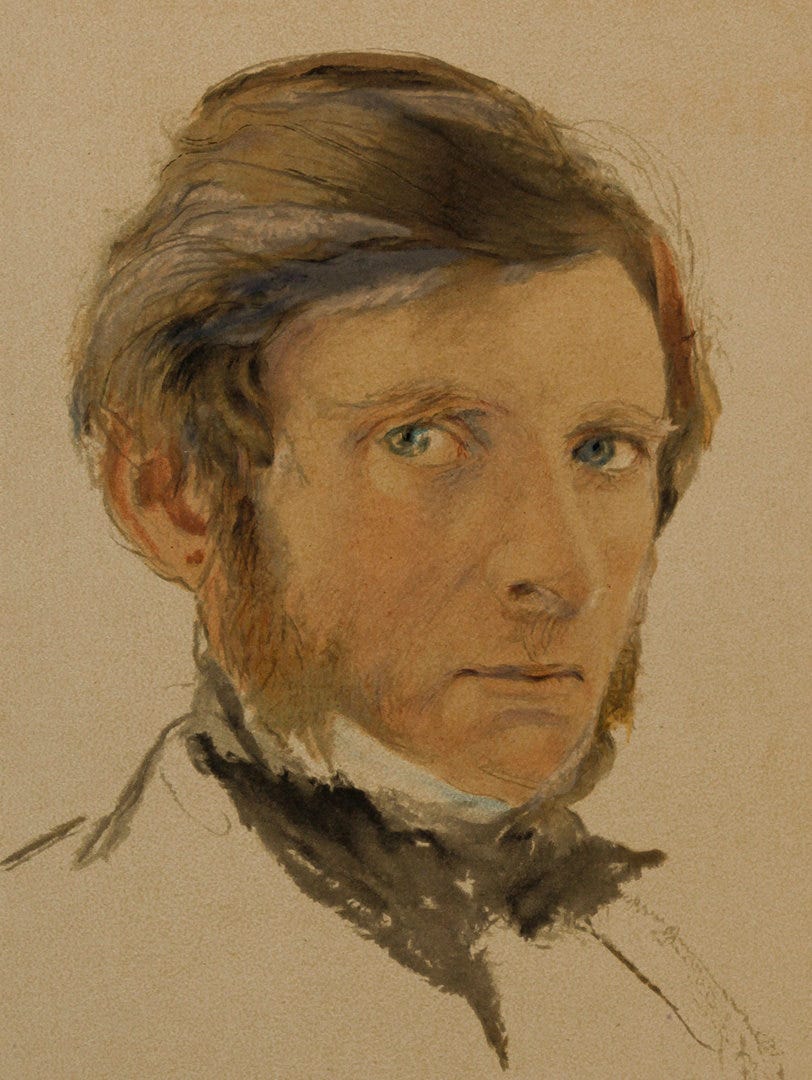

Tall and lean, he earned this name for literal as well as figurative reasons. His hawk-like nose was memorably large. It was also his great good fortune — an indispensible gift in the blending necessary for creating the best of all sherries.

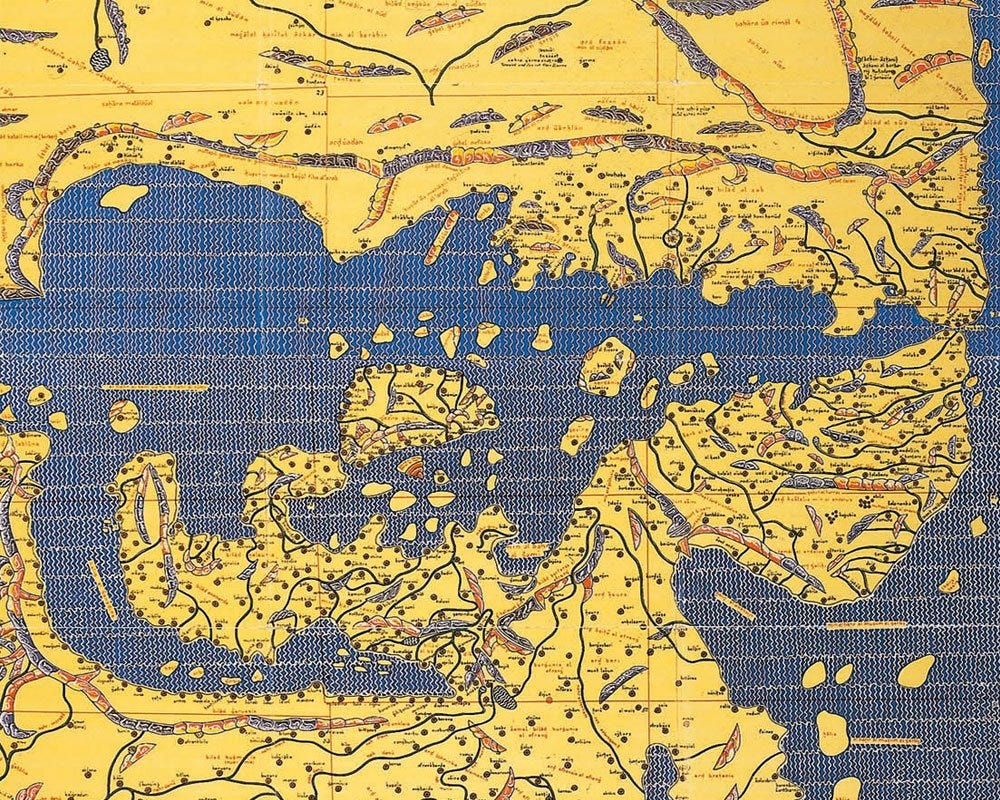

Since he was a young child, he could memorise aromas and tastes ranging from the freshly pressed must of Palomino grapes to the rich, old dry sherries called Olorosos dating from the 1730s when the company was founded by an Irish farmer Patrick Murphy and one Juan Haurie.

The company rose to fame and fortune in the early 19th century when Ruskin, Telford, and Domecq were leaders in the British sherry trade. However the senior partner Ruskin's son, John, decided to make a life writing on art and architecture — which he did with famous effect.

It was left to another partner, Pedro Domecq Lembaye, a relative of the Haurie family which had owned the firm since 1791, to expand the business.

In 1816 Pedro Domecq quarrelled with the Haurie family, bought the business and renamed it Domecq after himself.

José Domecq married in 1934 Angelea Fernandez de Bobadilla y Gonzalez (they had seven sons and five daughters) and he joined Domecq in 1939. He subsequently became a member of the board in 1957 and from 1994 until December 1996 was on the main board of Allied Lyons Domecq.

A group of British MPs meets El Nariz

In 1992, the British Heritage Group of peers and members of the House of Commons, travelled to Spain: highlights of the trip included a two-hour meeting with King Juan Carlos, and meetings with members of the government and the opposition, the Mayor of Seville in Expo year, and, finally, with Don Jose Ignacio Domecq.

Once the British group arrived at the Domecq winery — a colossal whitewashed warren of buildings, streets and cellars called "The Jerusalem of Jerez" — a septuagenarian hove into sight on an ancient Moto Guzzi “Hispania” motorbike, with a Jack Russell dog (as always) in a basket on the back.

José Domecq descended from his motorbike and greeted each of his guests with a ferocious handshake.

"The Nose" took the British parliamentarians round his 2,500 acres of vineyards in Jerez superior from which come the well known sherry brands of Fino La Ina and the Double Century range. Afterwards they were shown his wonderful collection of Andalusian horses; he was still an expert polo player well into his seventies.

But the crowning experience was being taken by Domecq into his vaults: they are regarded to be among the most spectacular cellars in the world and none would ever forget being given a taste of the many brandies still available there, including one made by the original Pedro Domecq in the year that Napoleon went to St Helena, 1816.

The world of Sherry

José Domecq's personal skills as a blender were stupendous and his dedication to quality and innovation resulted in the creation of some of the most exquisite sherries the world has ever known.

In an essay for Christie's Wine Companion (1987) he wrote:

Strolling through the bodeja dipping out old sherries which have rested undisturbed for generations, must be one of the most satisfying encounters a man can have with wine.

In the same essay he gave his view of the world thus:

in ancient bodejas one watches human egos come and go — all talking loudly about market trends etc in the jargon of the moment — while the wine ignores them all and silently ages, turning itself with our tactful guidance into the same lovely old perfection enjoyed by our ancestors.

In his book Sherry (1970), Julian Jeffs wrote:

At Domecq's bodeja there is a cask of Palomina that is well over 200 years old; it has, of course, been refreshed from time to time with old wine of the same style, but it is now practically black and is so strong in flavour that it cannot be drunk unless blended with a younger wine.

In the realm of sherry, José Ignacio Domecq's expertise was extraordinary: he was known for his meticulous approach to the solera system, a unique method of wine-aging achieved by blending sherries of different ages in order to obtain a harmonious and consistent final product.

His impact on the industry transcended his own family's business, as he generously shared his knowledge and techniques with fellow producers, ultimately elevating the entire sherry industry. His contributions earned him widespread respect and admiration, cementing his status as a legend in the world of wine and spirits.

During his lifetime, he fought ferociously to protect the good name of "sherry" against non-Spanish imitations, and won the war of nomenclature in Brussels in 1994 in establishing his point by European Directive (British sherry henceforth had to be described as "British fortified wine").

Five days before he died of lung cancer he had the energy to remove his oxygen mask and drink what he called "La Penultima Capita".

José Ignacio Domecq died in Jerez on 15 January 1997.

— Alberto @