Adorable Story #40: Henryk de Kwiatkowski

The Polish-born Aircraft manufacturer & broker whose life reads like a novel

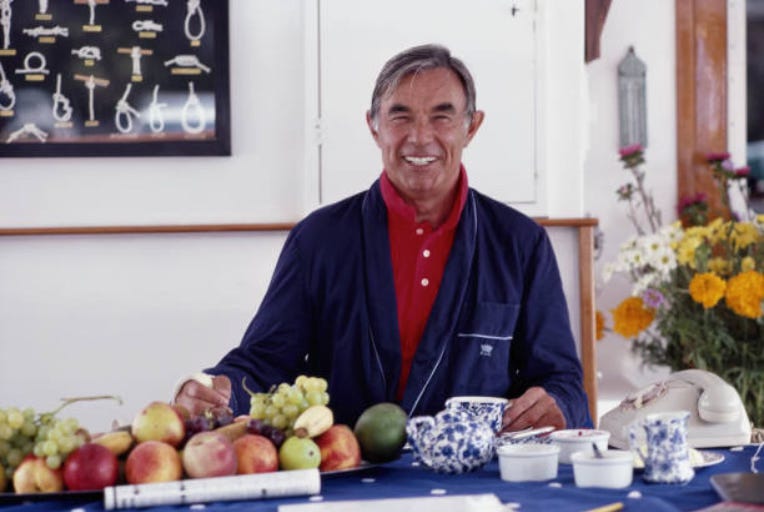

“He is very tanned, and has a full head of dark hair shot with silver. When he takes off his black-framed reading glasses, which make him look a lot like Felix Rohatyn, and flashes an eager, full-toothed smile, he bears a startling resemblance to illustrations of Genghis Khan.”

— Bob Colacello, Vanity Fair, 1992

Henryk Richard de Kwiatkowski was a Polish-born member of the Royal Air Force who became an aeronautical engineer, made a fortune in business in North America, and who owned the legendary “Calumet Farm”, one of the most prestigious thoroughbred horse breeding and racing farms in the United States, which throughout its history of over 87 years, has produced some of the greatest thoroughbred horses of all time.

If you aren’t subscribed yet, hit the subscribe button below to receive the Adorable Stories every weekend, directly in your inbox:

Origins

Henryk de Kwiatkowski was born in Poznań, Poland on February 22, 1924.

Albeit “de” — the Romance language prefix indicating an aristocratic background — doesn’t exist in Polish, he explained that his grandfather Frenchified the family name after fighting under Napoleon.

Henryk told of being awaken one morning in 1939 on his family’s farm in Poznan with news that the Germans had invaded Poland. His mother told Henryk and his brothers that “all of you have to go and fight against Hitler.” His mother was later arrested by the Gestapo, and he never saw her again.

At age 15, Henryk de Kwiatkowski joined the Polish resistance efforts, mostly fighting against the Russians.

“[W]hen the Russians entered Poland on September 17, I was in Kremenets, on the border with Bug. I remember that Sergeant Krzyszkowski taught us how to stop tanks. At that time I was a young boy scout, I went to a Jesuit school, where we were taught that you must not kill. We stopped Russian tanks in such a way that we put bottles under the tracks that ripped the chains preventing them from riding and causing the whole convoy to stop. We did it in great conspiracy, but in the end it failed and they arrested us at school before Christmas. We received a sentence for sabotage: 20 years of exile for heavy work in Siberia.

Siberia

Henryk de Kwiatkowski was captured by the Russian Army and promptly sent to a Siberian labor camp for prisoners of war.

“they handled us gently, because if it was the NKVD [the Soviet police, overseeing the country's prisons and labor camps], they would shoot us on the spot. They packed us into cattle cars and we rode for weeks. At the destination they said we would cut trees. They gave us axes and saws and took us to the workplace.”

After being imprisoned for two years in Siberia, Henryk met a doctor imprisoned there since WWI who asked him to be part of an escape effort.

“There I met a doctor from World War I, who had been developing an escape plan for years. Having trusted me, he showed me his plan. In the years 1941-1942 I memorized and repeated everyday the names of the places through which the train had to pass and I will probably not forget them until the end of my life: Kuibyshev, Almati, Tashkent, Kokan, Samarkand, all the way to the Caspian Sea and Iran.”

Henryk de Kwiatkowski managed to escape the labor camp and followed the escape route — by walk and the occassional train — through Russia, heading south as quickly as possible. It took him months and many of the fellow prisoners who escaped with him eventually were captured and forcibly returned to the labor camp in Siberia. During wintertime, Henryk managed to stay warm by boarding train cars as much as possible in order to avoid the rigid Russian temperatures.

“I was lucky again, in one of the first-class compartments there was only one passenger, a woman who saw me and invited me inside. I remember how she touched my lips and said: "What did they do with you, you still have mother’s milk on your lips"

It turned out that the compartment was specially reserved for the NKVD, and she was the wife of the head of the NKVD of Uzbekistan. She said she would help me. I asked about the town from the doctor's list, she said that there is Tashkent, Kokan on the way ... I was happy that I was going in the right direction.

This lady helped me reach Tashkent, where she lived and explained to her husband in what circumstances she met me. I lived with them for a month, and then her husband gave me papers so that I could escape from Uzbekistan through Kokan, Samarkand and the port city on the Caspian Sea, Krasnowodsk. I got there on a coal ship and sailed for Iran.”

Once in Iran, he contacted the British Embassy: he lied about his age and was then taken by British agents to Iraq, where he enlisted with the British Air Force.

After joining the British Air Force, Henryk was sent for basic training in South Africa.

Empress of Canada

After completing R.A.F. training in Durban, South Africa, Henrik de Kwiatkowski was sent to England on board the Empress of Canada (originally an ocean liner converted into a troopship during WWII).

On 14 March 1943 at 01.00 am, while en route from Durban, South Africa to Takoradi, Ghana, carrying Italian Prisoners of War (P.O.W.) along with a number of Polish and Greek refugees, the Empress of Canada was torpedoed by the Italian submarine Leonardo da Vinci, approximately 400 miles (640 km) south of Cape Palmas, off the coast of Africa.

The Empress of Canada was quickly sunk.

The shark-infested waters off the coast of Africa proved fatal for many of the prisoners and refugees aboard the Empress of Canada: of the approximate 1,800 people on board, 392 died. 149 of the fatalities reported were Italian P.O.W., while British rescuers were able to save 800 of those P.O.W. aboard (the Leonardo da Vinci herself would be sunk by British patrol ships two months later, with no survivors).

De Kwiatkowski survived and eventually reached England: he lied again about his age in order to join the British Royal Air Force in England, and flew numerous combat missions against the Germans.

During WWII, both his parents and four of his six siblings were killed.

He served with the Royal Air Force until 1947.

Post-war Studies

“I studied aviation engineering at King's College at Cambridge University, then a few months of sculpture in Florence, eventually I went to Canada at McGill University. In Canada, I started working for Pratt Whitney, a company that produced aircraft engines. In 1962, having 3,000 dollars, I opened my own company Kwiatkowski Aircraft Inc.”

After graduating in Europe, it was not easy for Henryk to move first to Canada and then to the US, because of the strict immigration quotas established by North American governments after WWII.

“I received a Canadian passport by a parliamentary decision, when Great Britain refused citizenship to Poles and ordered them to return to the country or resettle. I could not understand how Great Britain could deny citizenship to people who, together with the British, fought against Germany. Someone in Canada found out about my protests and I was given a passport.

It was equally difficult for Poles to come to the United States because they were given a smaller limit than Pakistani. I met John Kennedy, who was a senator at the time, and told him about it. He said that when he became president, he would remove this injustice. During the 1000 days of his presidency, he did not change any regulations in this respect, except those concerning immigrants from Poland.”

Used airplanes brokerage

In the 70s and 80s, Henrik de Kwiatkowski made millions as an independent broker of used airliners.

Among his extraordinary stories was one when De Kwiatkowski’s personally flew the Shah of Persia into and out of exile in Rome when Iranian prime minister Mohammad Mosaddeq briefly seized power in 1953.

Washington Times editor Amaud de Borchgrave was the Newsweek correspondent covering the Shah’s return to Teheran and met the Shah once the airplane landed in Teheran and confirmed:

“I went on the plane after it landed and interviewed the crew. Henryk was the pilot.”

De Kwiatkowski has always said that this service stood him in good stead with the Shah twenty years later, when he pulled off the deal that put him into spotlight: selling nine used 747s from TWA to Iran for USD 183 million and earning him a USD 20 million commission.

De Kwiatkowski later explained that he negotiated that deal directly with the Shah over a late-night backgammon game at the Hilton Hotel in Teheran.

“I remember when I went to Iran with 24 hours to conclude the transaction. I signed the contract while playing backgammon. It was not a simple transaction because it was connected to a nuclear reactor contract, worth billions of dollars. I did everything while sitting at the Hilton Hotel in Teheran. Waiting for the call with information about a positive result, I excitedly scratched my name on the wall. It was probably one of the most exciting moments in my life.”

Horse breeding

Henryk enjoyed playing polo, saying that his love for horses went back to the days when his family’s farm bred horses for the Polish cavalry.

In the 1970s he bought a 2-year-old filly named Kennelot, which became the foundation mare to Kennelot Stables.

Among his horses were Conquistador Cielo, the 1982 Horse of the Year in North America, Danzig, a highly influential stallion, and Danzig Connection, who won the Belmont in 1986.

“The Queen of England loves horses very much, she has a great knowledge of pure-bred and racing horses. She often came to Kentucky and saw several of my horses, she particularly liked "Danzig". Today all my horses in England are in her stables. The Queen’s coach is my coach today.”

Calumet Farm

In 1992, de Kwiatkowski came to the rescue of Calumet Farm, a historic thoroughbred farm that was USD 100 million in debt and had filed for bankruptcy. The Kentucky farm had bred eight Derby winners, but its serious financial problems threatened its future.

Henryk bought it for the bargain price of USD 17 million and promised:

“I won’t change a blade of grass.”

He said that the farm’s landscape reminded him of his Polish homeland.

De Kwiatkowski’s actions made him a hero among horse lovers and Kentuckians. Many years after the purchase, people would still stop him on the street to thank him for keeping the landmark intact.

Art collecting

An art collector who favored the Impressionists, his collection included works by Paul Gauguin, Georges Braque and Claude Monet.

Kane and Abel

Henryk de Kwiatkowski was the basis for the character Abel Rosnovski in the 1979 Jeffrey Archer best-selling novel “Kane and Abel”: the novelist spent two entire days tape-recording him for his novel which tells the story of a poor Pole who miraculously escapes from a Siberian prisoner-of-war camp.

Henryk de Kwiatkowski died of pneumonia at his home in Lyford Cay in March 17, 2003. The day before he died, his horse, Region of Merit, won the Tampa Bay Derby.

After his death, Calumet Farm was passed down to his family members as a group of trustees.

Following Henryk de Kwiatkowski’s death at his home in Lyford Cay in March 17, 2003, John Asher, a spokesman for Churchill Downs said:

“He did a lot of things in thoroughbred racing, but saving Calumet Farm was something the industry will be eternally indebted to him for.”

— Alberto @

Do you know anyone who would love to read this Adorable Story? Show your support by sharing Adorable Times’ Newsletter and earn rewards for your referrals.