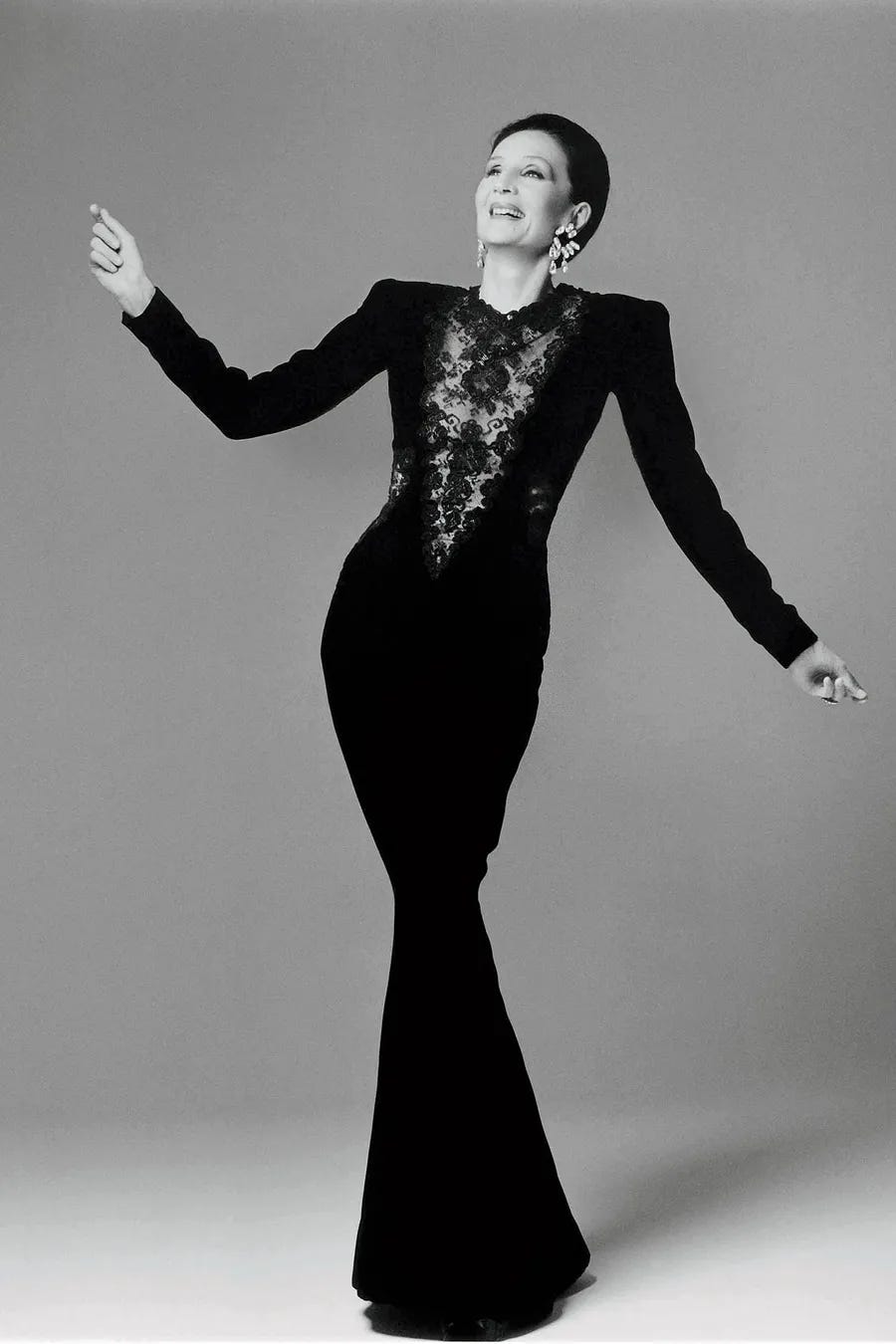

“The Last Queen of Paris”

— Valentino Garavani

Family

Jacqueline de Ribes was born on Bastille day, July 14, 1929, in Paris, France into an aristocratic family: she is the daughter of Count Jean de Beaumont (1904–2002) and Paule de Rivaud de La Raffinière (1908–1999).

Her father was a fighter pilot and a member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) for 48 years. Her mother, Paule, was a socialite, translator of Hemingway in French and a well-known figure in the Parisian elites.

During his life, Count Jean de Beaumont almost doubled his wife’s family fortune derived from their investment house, Rivaud Group, originally founded in 1910. Among their most lucrative businesses, there were the investments in rubber, banana, and palm-oil plantations in Africa, Indonesia, and Indochina.

Jacqueline adored her father whom she described as “a seducer, a charmer, with a fantastic body”, while she did not have a great relationship with her mother who regularly mocked her for her unusual features (especially her long nose) and for her aspiration to become a ballerina.

“My mother kissed me just once in my childhood,” Jacqueline once noted “I had the feeling always of being insecure—so I was always bumping my soul and my head.”

Jacqueline spent most of her childhood with her maternal grandfather, the Count Olivier de Rivaud de la Raffinière: “He had châteaux, yachts, racing stables, women and cars”— including a special 1932 all-terrain Citroën, equipped with tank-type tracker-rollers to climb up the slopes he liked to bobsled down during winter-time.

During the Spanish Civil War of the 30s, loyalist refugees used to cross the border, at the Bidasoa River, into France, and land in the gardens of her grandfather’s summer compound in Hendaye, on the Côte Basque, very close to the Atlantic Ocean and the Pyrenees mountains.

On October 16, 1938, Olivier de Rivaud died of cancer at 63 years old and soon thereafter WWII started.

WWII

At the start of WWII, the Counts de Beaumont sent Jacqueline and her siblings together with their Scottish nanny from Paris to Hendaye (near the Spanish border) in the hope for them to avoid the worst aspects of the war.

As soon as they arrived in Hendaye, the Scottish nanny, as a British national, was captured by Nazi officials and locked-up in a forced-labour camp.

The parents then sent a French nanny to guard the kids and they all lived together in the concierge’s cottage, while the Gestapo occupied the main building of the Hendaye’s mansion (Jacqueline recounted that from her room in the concierge she could hear tortures occurring in the mansion).

In 1943, the parents moved Jacqueline and her siblings to the chateau of the Count of Solages, in the center of France. Also that chateau was shortly thereafter occupied by German officers until the American Army finally liberated it in 1945.

Jacqueline completed her education at the convent of Les Oiseaux, in Verneuil: her uncle, Count Étienne de Beaumont, the avant-garde-art patron and party host, took his adolescent niece to see his friend Christian Dior shortly after the designer opened his couture salon in 1947, and said to the French couturier: “I put lots of hope in this little girl”.

Édouard de Ribes

In 1947, Jacqueline met Édouard de Ribes at a friend’s luncheon party in Saint-Jean-de-Luz, not far from Hendaye.

Édouard remembered: “I saw this gazelle and immediately fell in love”.

The de Ribes was a family of financiers, a conservative clan, extremely prudent with money and they considered the Beaumonts to be excessively worldly.

In 1949, at the age of 19, Jacqueline married Édouard.

Jacqueline’s father-in-law described her as a “cross between a Russian Princess and a girl of the Folies Bergère.”

Together, Jacqueline and Édouard had two children: Élisabeth, born in 1952, and Jean, born in 1956.

New York

“An ivory unicorn”

— Yves Saint Laurent

In the early 1950s, Jacqueline visited New York for the “April in Paris Ball” at the Waldorf-Astoria. While her husband, Édouard, was in a Wall Street meeting, she had lunch with the French-born, Mexican multi-millionaire art collector and interior decorator, Charles de Beistegui.

Diana Vreeland, the then-fashion editor of Harper’s Bazaar, saw Jacqueline and invited her for a photo session with photographer Richard Avedon.

“She said, ‘We’d like Avedon to take your photo tomorrow.’ The next day I went to the hairdresser. I got false eyelashes, curled my hair. When I showed up at the studio, Diana said, ‘I want you to be how you were yesterday!’ She peeled off the eyelashes, combed out my hair. And she made me a braid! Diana Vreeland helped me be authentic. She taught me confidence. And the picture became famous.”

This iconic profile picture of Jacqueline, which featured her elongated neck, large almond eyes, and thick braid, was later published in Life magazine and Avedon’s anthology “Observations,” with commentary by Truman Capote.

Capote compared Jacqueline, Babe Paley, Marella Agnelli, and Gloria Vanderbilt to “a gathering of swans.” Avedon commended Jacqueline’s “perfect nose” and added “I feel sorry for near-beauties with small noses.”

Jacqueline stated it was between 1950 and 1955 when she developed her unique style, with the most significant transformation happening between 1953 and 1954.

During a 1955 visit to New York, where she attended the Knickerbocker Ball in a Dessès gown, Jacqueline de Ribes caught the eye of fashion designer Oleg Cassini (former partner of Grace Kelly, previously featured in the Adorable Story #21). Impressed by her elegance, Cassini saw in her a latent designer and invited her to create designs for him. Back in Paris, Jacqueline started drafting dress patterns with the help of studio heads from Patou and Balenciaga.

As she couldn’t afford silk, she made the dresses in muslin cotton and packed them for Cassini. Because she needed to attach sketches of the designs to each box and couldn't draw, she hired a young Italian artist from Jean Dessès studio, Valentino.

Valentino sketched the designs, often adding his own touches, and made frequent complaints about his living conditions in Paris. Despite his complaints, Jacqueline encouraged him to stay in Paris to advance his career.

Three years later, Valentino opened his own couture house and Jacqueline started buying clothes from him.

In 1956, she was named to the International Best-Dressed List in the Professionals category and was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1962. Friends and acquaintances regarded her as the epitome of French elegance.

“When everyone still cared about the way they dressed,” said her friend Jayne Wrightsman, “everyone wanted to dress like her and look like her.”

Skiing

When Jacqueline de Ribes married Édouard, she made it clear that she would spend three months out of each year skiing in Megève, Kitzbühel, St. Anton, Saint-Moritz, or Cervinia. Her friend, Marina Cicogna, admired Jacqueline’s grace and athleticism in activities such as skiing, swimming, dancing, and skating, saying she was “as good as the best men.”

Italian designer Emilio Pucci, a former national ski team member, spotted Jacqueline skiing in St. Anton dressed entirely in pink, a standout among the functionally-dressed crowd. This encounter led to a professional collaboration in which Jacqueline designed evening dresses for Pucci. They traveled together to Chicago and then to Dallas to visit Neiman Marcus, where Stanley Marcus introduced Jacqueline as Pucci's new assistant, much to Pucci’s chagrin. Jacqueline worked with Pucci for two seasons. He affectionately referred to her as “Giraffina,” or baby giraffe, and predicted that she could fill Christian Dior's shoes if she so chose, a prophecy that left a lasting impression on Jacqueline.

Business Endeavours

Jacqueline de Ribes often recounted that many of her endeavours were met with disapproval. These included penning a column anonymously for Marie Claire and leading the international committee of the Embassy Ball, a charity event for children with disabilities.

Her husband, Édouard, was particularly upset when she took over the International Ballet of the Marquis de Cuevas after the death of its founder, George de Cuevas. The ballet company had seen success under the stewardship of Raymundo de Larrain, de Cuevas’s nephew, with a production of “The Sleeping Beauty” and the participation of dancer Rudolf Nureyev.

Upon de Cuevas’s death, his wife withdrew her financial support for the company. Jacqueline stepped in as the new manager, partnering with de Larrain.

They ambitiously remounted Prokofiev’s “Cinderella”, featuring 17-year-old ballet student Geraldine Chaplin, daughter of Charlie Chaplin.

To meet the production’s substantial costs, Jacqueline solicited donations from friends, an activity her husband and in-laws found distasteful. However, the production was a sellout. Jacqueline donated her old Balenciagas to the ballet company's dancers and a large portion of her haute couture collection went to the A.N.F., a French association for aiding impoverished nobility.

After three years, Jacqueline decided to dissolve the financially draining Ballet de Cuevas.

Around 1970, Jacqueline de Ribes expanded her foray into show business by co-producing three segments for French television based on Luigi Barzini’s 1964 book “The Italians” and two UNICEF variety shows featuring renowned actors such as Marlon Brando, Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor, and the Red Army Chorus.

During this time, she befriended Luchino Visconti, who was in Ischia developing a film adaptation of Marcel Proust’s “Remembrance of Things Past.” Visconti considered casting Jacqueline de Ribes for the role of the Duchesse de Guermantes, the witty social arbiter of Paris. Visconti admired her grace, style, and laughter. However, his death prevented the film from coming to fruition.

Fashion Design

In 1982, Jacqueline announced to her family and close friends, Pierre Bergé and Yves Saint Laurent, her intention to pursue a career as a fashion designer.

Despite initial skepticism, she debuted her first collection during Paris Fashion Week in 1983 in her own house, a move that was unprecedented at the time. Her designs were well-received and quickly gained commercial success, leading to an exclusive three-year contract with Saks Fifth Avenue.

By 1985, her business was grossing USD 3 million annually and was featured in over 40 stores across the U.S. She had a high-profile clientele, including Joan Collins, Cher, and Nancy Reagan.

In 1986, Japanese cosmetics conglomerate Kanebo bought a minority stake in the company, but the relationship quickly soured due to disagreements over design direction.

Jacqueline then began to suffer from debilitating back pains and was hospitalized for nine months, leading to her missing two collections. She was then unable to walk for three years (1994-1997) following a hemilaminectomy (a surgery that removes part of a vertebra to enlarge the space in the spinal canal and relieve nerve compression or pressure). In the midst of her medical struggles, she was diagnosed with celiac disease.

In 1995 she was forced to finally dissolve her fashion company.

In 1996, her family, particularly her husband Édouard and son Jean, faced legal troubles as the Rivaud Group, under Édouard’s leadership, was subjected to an investigation by the French government for tax evasion. The government levied an unprecedented 30m Francs fine (10m USD at the time), which the family (very surprisingly) was able to pay, but the scandal led to corporate raid of the Rivaud Group by billionaire Vincent Bolloré.

Her husband Édouard died in 2013 at 90 years old.

In 2015, the The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Anna Wintour Costume Center dedicated an exhibition to Jacqueline’s most iconic looks with the name “Jacqueline de Ribes: The Art of Style”.

Marina Cicogna summed up Jacqueline as having the manners and language of traditional French aristocracy, yet embodying a contemporary, always youthful spirit.

Today, at 94 years old, Jaqueline still divides her time between Paris and London.

— Alberto @

Fantastic Jacqueline!